Winner of the 2020 Saier Memorial Award in Fiction

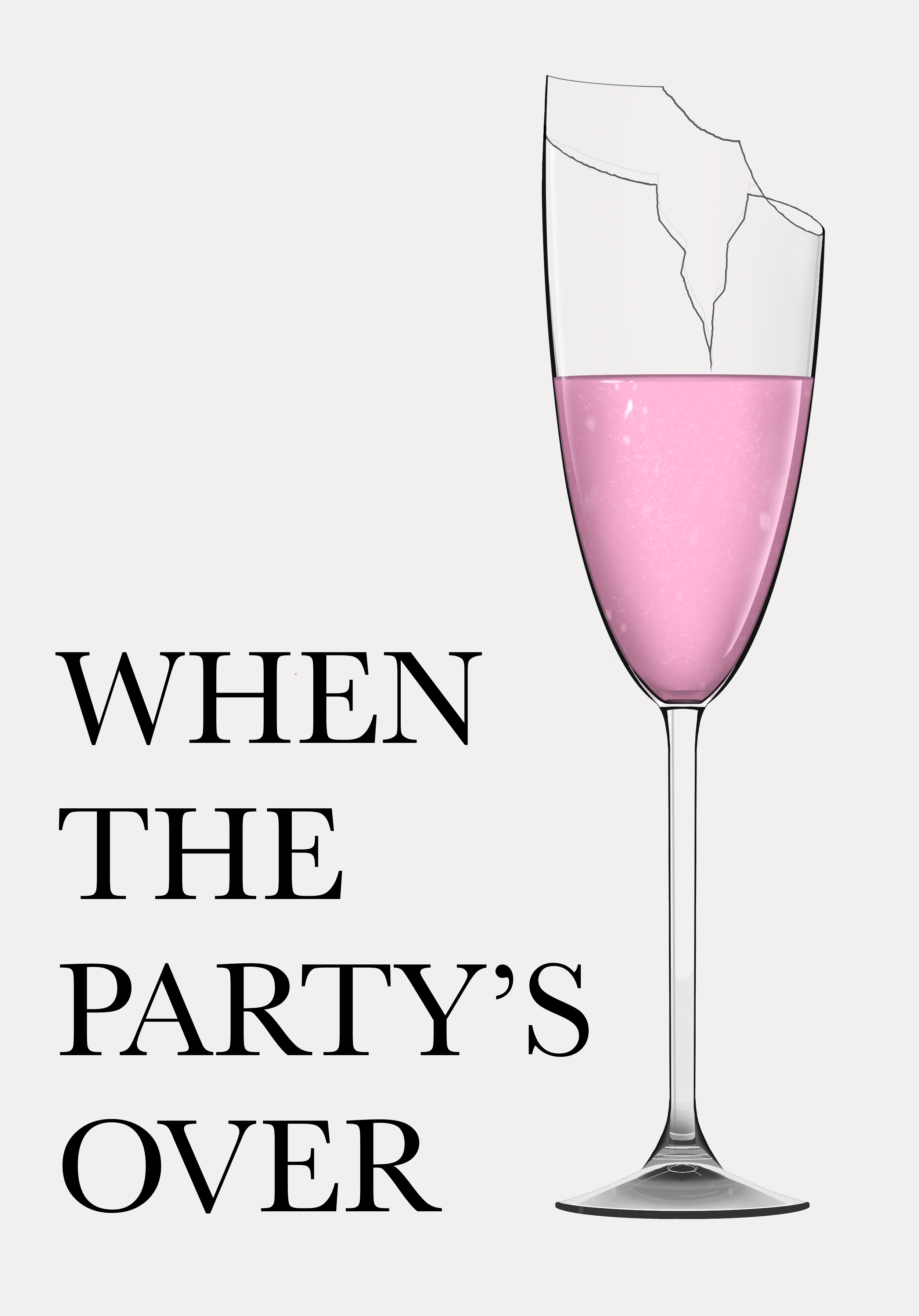

If she closes her eyes, she can see it clearly: the pink lemonade in the crystal-clear flutes, tiny sausages wrapped in phyllo, fairy lights spiderwebbing across the ceiling. SABRINA’S SWEET SIXTEEN, stretched in lacy letters out over the cake table.

The cake, of course, is from Beverly’s, lemon with vanilla buttercream. Sabrina Haverford smells it from all the way up here in her bedroom, even though the cake table is a floor below in the family ballroom. If she tries hard enough, she can almost pretend she’s down there with the guests––dancing, laughing, smiling. Can almost forget the Gordian knot in her chest.

Can almost prevent herself from imagining what would happen if she sliced it through. Sharp edge of steel cutting through tangled mass.

Because why not? Alexander the Great did. Whoosh. Problem solved.

Sabrina turns over in her bed.

Problem not solved, she can hear her therapist saying in her head. He’s never actually said that to her, but he might. She likes that he doesn’t treat her like she’s made of glass. She hates that she sometimes feels like she is. The smallest things happen, and then she shatters.

Problem not solved, she reminds herself. Problem not solved. Still, her lungs constrict. Her heart stutters. Her world spins.

As if on cue, someone knocks on the door.

“Who is it,” Sabrina manages to say.

“It’s Cooper,” the person behind the door says.

Sabrina doesn’t answer, because too many thoughts have rushed her brain.

Twenty people, her mother said, one month ago. That’s all I ask. I’ll take care of the rest. Mrs. Haverford smells like rosewater and champagne. She walks with her head held high, commands an army of maids and butlers and gardeners to manage the family’s twenty-acre property. She throws summer soirees and annual galas, runs a women’s book club and sits on the board of directors for three different charities. And now, after what happened with Sabrina, she’s officially the family’s damage control specialist. Hence, the Sweet Sixteen. It makes sense in a kind of twisted way. Normal daughters have Sweet Sixteen parties, and the Haverfords must pretend that they have a normal daughter, for the sake of preserving the family name, even if they know that they don’t. And while Mrs. Haverford doesn’t expect Sabrina to act normally, she at least expects her to play along when the time comes. Only twenty people, she said. Send me a list by tonight.

So Sabrina came up with the guest list. Cooper, of course––her best friend, even after everything. A few of her dad’s business partners’ kids. The scholarship students in her grade from Hamilton Prep, because her mother might not know who they are or care to invite them. But as she added their names to the list, Sabrina cringed. If they came to the party and walked through the house, saw her life for themselves, they’d probably think she was stuck-up and spoiled and dramatic. And they wouldn’t be wrong. Sabrina grew up swimming in her family’s indoor pool during the winter and outdoor pool during the summer. Her mother’s dinner parties are always fourteen-course affairs, the meat tender and dripping with fat, the lettuce crisp and hand-washed, the last course a tall cake with melted chocolate pouring down the sides like a fountain. As part of the grand finale, the Haverfords’ butler comes in and douses the cake with alcohol, then lights it on fire, casting a bright warm glow into the dining room as the guests ooh and ahh. Sabrina loved this spectacle when she was younger; she assumed that everyone else grew up with this exact same experience. But the older she’s grown, the more she’s learned how far this is from the truth, and the more the overt excesses of her family pain her. She stopped going to those dinner parties last year. The Haverfords’ swimming pools sit empty, still and quiet. Sometimes, when she’s lying in bed, she squeezes her eyes shut even when she’s not tired, because she doesn’t want to think about how cavernous her room is, how every square inch that she doesn’t occupy feels like a waste. She aches to be in a place where she takes up the exact amount of space that her body fills. No more, no less. A box, maybe. A cupboard. A coffin.

Cooper knocks on the door again. “Sabrina,” he says, more insistently.

“Yes?” she says.

“Are you okay?”

Short pause. Cooper won’t believe her if she says yes, but he’ll want to come in and talk to her if she says no. “I’m all right.”

“Do you want to talk about it?” he asks.

Sabrina turns over in her bed. “I’m fine. I’ll be down in a minute.”

Both of them know this is a lie.

She knows he’s scared of what might happen if he presses her. But he’s also scared of what might happen if he leaves her alone.

Cooper knows all about the Gordian knot.

“Text me if you need anything,” he says, finally.

Sabrina says, “Thank you.”

She hears his footsteps fading out. When their sound disappears, her chest clenches again.

Four months ago, they went to Olivier’s, the two of them. Their one-month anniversary. Sabrina, in a gold satin Chanel with a sequined bodice. Cooper in his tuxedo, grinning from ear to ear. When he’d brought up the idea of going there, Sabrina had tried to protest; it was too fancy for a one-month anniversary, she said. Cooper insisted, though, so Sabrina tried to go along with it.

But when they got there and he pulled out the chair for her, Sabrina understood, acutely, under the warmth of his gaze, that carrying this on any longer was unfair to him. She couldn’t keep lying and telling him that she was fine, but if she told him what was going on, he’d want to help, and that would only drag him down. Sabrina knew she was many things––snotty, spoiled, privileged––but she was determined not to be a burden.

Cooper ordered a steak; Sabrina asked for escargot. But by the time the entrees came, he was pleading.

“Can you at least,” he said, “give me a reason why?”

He was close to tears, Sabrina could tell; he still wore his heart on his sleeve, especially around her. She’d only ever seen him cry once, about his parents.

But now he was clutching her hands, candlelight casting a delicate glow over his face, which had recently sharpened into something less childlike, more handsome—more beautiful, honestly, which was something Sabrina couldn’t deny. She liked him almost as much as she hated herself.

Her throat thickened. The waiter set their dishes silently on the table, then left without grandeur. What was she to say? “Cooper, I…”

She couldn’t leave him without an explanation; she couldn’t lie to him, either, not Cooper, her best friend of ten years—Cooper, with whom she’d built pillow forts when they were younger. Cooper, who on that fateful day showed up at her house, walked upstairs and confessed that he’d liked her for years and years and years and would she please go on a date with him, just one date and then if it sucked they could pretend it never happened and go back to being friends again. The date had gone sufficiently well enough for Sabrina to agree to be more than friends, but the storm clouds had been gathering even then. She’d just fooled herself into thinking she could ignore them.

By that point, though, they were undeniably present, and Sabrina couldn’t drag someone else into the tempest with her. She cried before he did. She wept into his shoulder, left tear stains on his thousand-dollar jacket. She made him promise to send the dry-cleaning bill to her house. Then she told Cooper the truth: about how every day, she thinks about how it would probably be so much better for the world, for everyone, if she didn’t exist.

When the party’s over, she thinks now in the darkness of her bedroom, there will be a smashed mini sausage on the floor. Someone will have accidentally dropped one, then stepped on it, crushing it into a gristly pancake. A maid will sweep it up, leaving a shiny oily spot on the floor for another maid to mop.

A few of the fairy lights will flicker out. Her mother, in disgust, will order the staff to throw them away, just like she has them throw out yards and yards of Christmas lights every year. Nobody will point out that you can replace the bulbs without having to replace the entire string.

A few guests might wonder about Sabrina. “Where is she?” they’ll ask.

Mrs. Haverford will have some answer ready. “Oh, she’ll be down shortly,” or, “She wasn’t feeling well, but she still wanted to have the party.”

More than a few are bound to notice that although there’s a cake, there’s no happy birthday song. The gifts are taken automatically by the housekeepers; Mrs. Haverford will open them later, keep what she thinks Sabrina wants, then give away the rest.

The Gordian knot tightens.

Sabrina wants to throw up.

She throws off the covers suddenly; they’re too heavy. She marches over to her closet, fumbles a bit, turns on the light. In the corner, the dress. Her mother had insisted on buying her one for the party—just in case, she’d said, just in case. Like Sabrina hadn’t just come home from the hospital, like the two of them hadn’t been there by the bridge that one night, Sabrina sitting on the side of the guardrail, her mother screaming at her to stay put. When she thinks about it now, that night feels like a dream, but the reason why she hadn’t jumped was because the moment itself had felt real, for once. But then the month in the hospital happened, then the therapist, and the medication, and all of that had rid that moment of its realness, and rendered it part of the narrative. Sabrina is ill, Sabrina isn’t fine, but she’s getting better, she’s trying to be. And that’s the thing, too, is that she’s trying to be.

Sabrina’s hands are shaking. Why. Can’t. You. Pull. Your. Self. Together. She rips off the pajamas, yanks on the dress, zips it up, the cloth getting caught on the delicate zipper. She tugs at it, one, two, three—

Rip.

What a quality dress. What a quality, quality, quality dress, that the cloth will be so delicate she can rip it—she! a girl who cannot get out of bed! She who cannot cannot cannot think of how many people are downstairs, milling around, thinking they’re waiting for her, when in reality they’re waiting for the ghost of a girl she’s never been, the girl who wears pretty dresses and sips pink lemonade and laughs, when really she is dying, suffocating, drowning, hunched over, bent down, crushed by the weight of the world, and oh God, how dare she feel this way. How dare she feel this way when she has everything at her disposal, and nothing to lose. How dare she feel that she has nothing to gain, and that everything is nothing. But all of this does mean nothing, doesn’t it?

Doesn’t it? she feels like screaming at herself. She catches a glimpse of herself in the full-length mirror installed on the wall of her closet. She looks crazy: clumps of hair matted this way and that. The poor ripped dress, Oscar de la Renta, must’ve cost a pretty penny and look, the poor little rich girl ripped it in a fit of rage. A fit of self-centered, impatient rage. This would be a good scene on a reality television show: how messy everyone is, you know? Regardless of socioeconomic status? Rich People are People Too! Oh, how viewers would laugh at her: too soaked in her own privilege to keep her head above the water.

She sags against the wall. How nice would it be, she thinks, to take a break from your own life. To never feel the poison of your own thoughts.

I would sell my own soul, my own self-awareness, my own life, if that meant I could finally have some peace.

In the distance, someone knocks on the door.

Sabrina wakes up. She’s face down on the carpet inside her closet, still wearing the ripped dress. She flips herself over weakly. “Come in.”

She hears footsteps, then the sound of Cooper’s voice. “Where are you?” he asks.

“Closet.”

He looks relieved when he sees her. “Oh my god,” he says. “Are you okay? What happened?”

She rubs her eyes, sits up. “Nothing.”

“Everyone’s gone,” Cooper says. Then, in a softer tone, “We all missed you.” He holds out his hand, an offering. Sabrina shakes her head.

He sits next to her instead, cross-legged on the carpet. “How are you feeling?”

She swallows the temptation to lie. “Not well.”

“People asked about you. They wanted to know if you were okay.”

Sabrina nods. She feels the manic energy slowly leave her body, seeping into the floor. “I’m sorry,” she says.

“For what?”

“For everything.” She emphasizes the last word, meaning, everything. “I just feel bad for putting everyone through this. Whatever this even is.”

“It’s not your fault,” he whispers back. “They get it.”

“I don’t think my mom does,” she says. “She keeps trying to pretend that everything’s fine. She bought me a car.”

Cooper coughs. “A car?”

“A car,” Sabrina says, and then, suddenly, she giggles. Across from her, Cooper’s face breaks into a smile. “It was nice of her, but I don’t leave my house! I don’t even have a license or a permit. What am I supposed to do with a car?”

“Maybe she’s trying to make you feel better,” Cooper says.

“Maybe.” Sabrina’s smile slips off her face. “But I think all of this is her way of pretending that I’m okay, and her way of covering for me until I get ‘better.’ But I don’t know if I ever will.”

Cooper leans forward and looks at her directly in her eyes. “You will,” he says, with force. “You’ll get better. It’s just a process.”

Sabrina tries to believe this. They sit in silence for a moment.

“How are your parents?” she asks. “We haven’t talked about—I haven’t asked about them in a while.”

Cooper grimaces. “Still not talking to each other. Still living in separate wings.”

“You know you’re rich,” she says, “when your parents sleep in different wings of the house, let alone different rooms.”

He rolls his eyes, but he’s smiling now, too, which is encouraging, so she keeps going. “You know what normal couples do? They make each other sleep on the sofa. In the living room. I’ve seen it on TV.”

“I’ve actually heard them arguing over which side of the house they can take,” Cooper says. “The Mauve Wing? Or the Lavender Wing?”

“Red pill? Or blue pill?” she says, and now both of them are laughing again, at the ridiculousness of their world.

“I’ve been wondering about it a lot,” he says. “Why they need to do that. It seems unnecessary.”

Sabrina turns around, leans back so that her head is propped on his shoulder. “I think some people’s worlds are too small for them,” she says. “So they think making it bigger and grander will make them feel more whole. And then some people’s worlds are too big, so big that it feels like they’re getting swallowed by them.”

She feels him hesitate.

“Is your world the right size for you?” he whispers.

For a long, tantalizing second, Sabrina wants to say yes. This is a good moment, she knows, and in the good moments she feels most hopeful. But the lows come quickly, too, and right now they seem as if they never will stop coming.

So she settles for the middle answer, which is closest to the truth.

“I don’t know,” she says. “Maybe.”