Sometimes I wonder how I will feel when my parents die.

I acknowledge that conjecturing about such a thing doesn’t make me a special person. In fact, I bet that almost everyone has thought about their parents dying in some capacity. But lately, I’ve been spending a little too much time indoors and in my head. So, I wonder.

I know I’d be sad, go through the agonizing stages of grief. (Of course I would; I’m not a terrible person). But there is also a part of me, microscopic, that thinks that along with all the sadness and ache, I’d also feel a bit of relief.

So, maybe I am a terrible person.

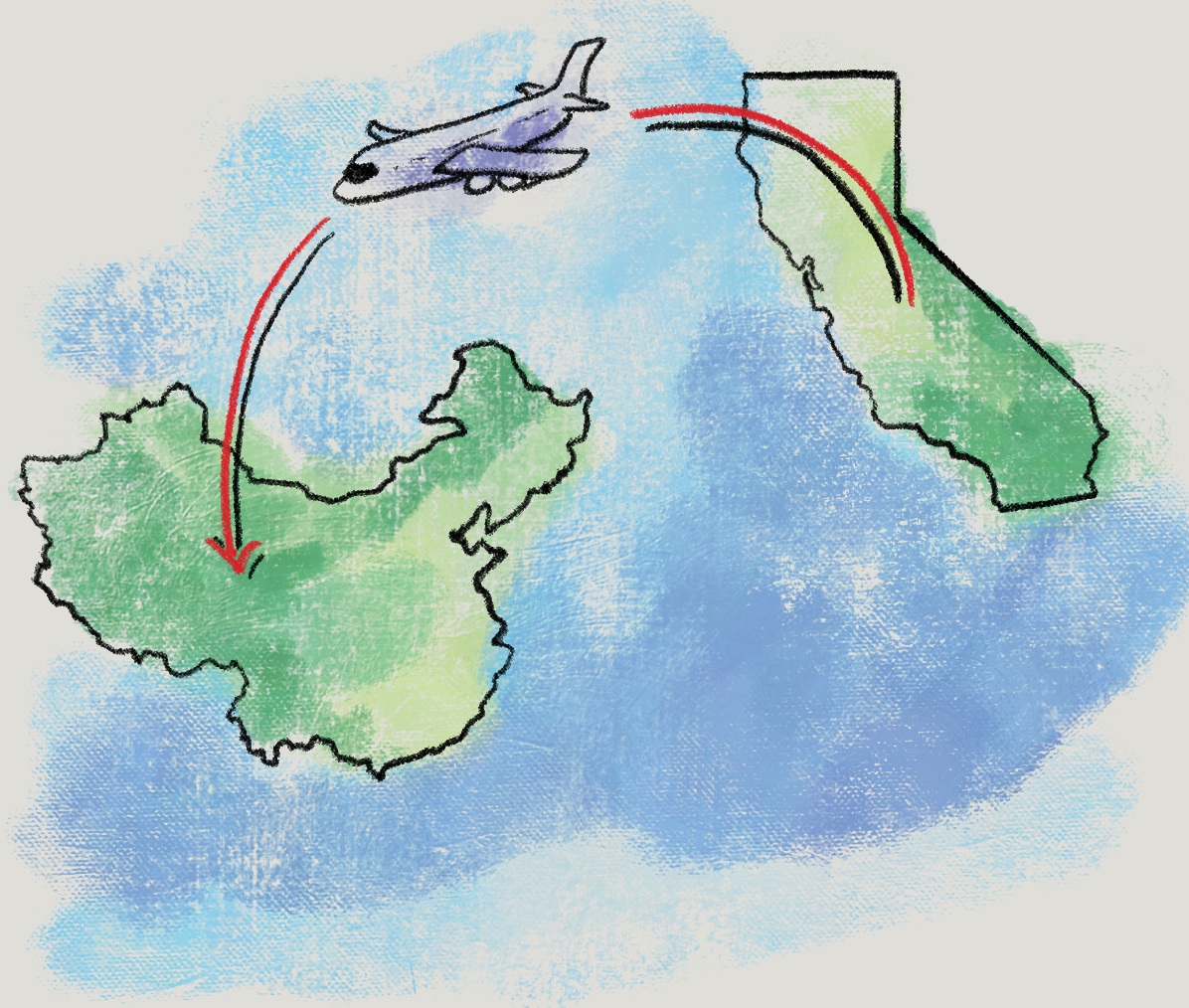

When I was 17, in the mellow heat of late California springtime, I went home after school one day and was immediately told to start packing. My dad, anxious, said, “We’re flying to China in two days.” I already knew what was happening. For two years, my grandfather had struggled with gastric cancer. Three months before the end of the school year, my mom, an oncology nurse, had gone back to China to take care of him. I never asked, but during the early days of his diagnosis, I assumed that she thought taking care of her father was her sole burden to bear, despite having two brothers, since she had experience taking care of cancer patients. Did she feel she neglected him? Pursued a “better life” and left her family in the dust?

We flew to China on a Saturday. After a grueling 16-hour flight, my dad, sister, and I took a train ride to my parents’ hometown, a small rural village eight hours south of Beijing. On a bullet train, the trip takes only two-and-a-half hours — not nearly enough time to mentally prepare for the coming weeks. Upon arrival, my oldest uncle met us at the train station to take us to the hospital. We would be saying good-bye to my grandfather soon.

The concept of China is something of a mystery to me. It’s one of those places that I know but I don’t. Every other year until I was ten, I spent my summers at my parents’ old homes. Some of my fondest childhood memories consist of playing with my cousins with whom I couldn’t even communicate. I know China because I have felt China — in the dust that collected in my hair and on my clothes from the unpaved streets; in the lukewarm water that my grandpa would collect from a local well and bring to our shower; in the sizzling heat that would radiate off the enormous wok my grandmother used in the kitchen.

And yet, despite having grown up going to China frequently, I am still a stranger. The first night of every visit, family friends stop by in a non-stop barrage, inquiring, “Do you remember me? Do you remember me?” Even if I don’t, I feel obliged to say yes. The women in my family grab my wrist, squeeze, and say, “She’s getting a little fatter!” I can never tell if this is a compliment or an insult, or a little bit of both. I think my parents, with their Western-trained ears, always think those comments are in poor taste, but I don’t care. I’m just happy to see everyone again. When I’m there, I am a guest. I can tell because when I visit, my grandma fishes out an old fork and knife set reserved for my sister and me. And yet nothing made the fact more obvious than my own grandfather’s funeral.

My grandfather died the day that we arrived. I’m not a hugely spiritual or superstitious person, but I believe he was waiting for his whole family to be with him before he let himself rest.

Traditional Chinese funerals are an exhaustive affair. They last a week at minimum, with rituals and events happening throughout the entire day. Almost as soon as my grandfather died, we were whisked back to my grandmother’s home to start preparing. When we arrived back, my cousins gave me a white head scarf and white cape-like drape to wrap around my shoulders. They asked, “Do you have anything white to wear?” I pretended to check my suitcase, but I already knew — everything I had packed was black.

I learned that evening that white is the color of death in China. Funny, I thought. Where I’m from, white is the color of life.

Luckily, my mom had a pair of white jeans and a neutral shirt that I could wear. The rest of the week was busy — during the day, villagers from the small town walked into our courtyard and stopped by my grandfather’s casket, which was kept in the living room, and presented food and gifts to him. A constant stream of strangers milled around the kitchen, the halls, the dining area. Except these people weren’t strangers. My family knew all their faces. The only unfamiliar person was me.

At night, our family poured out into those unpaved roads that I knew from my childhood and marched across the town. My oldest aunt wailed at the top of her lungs, screaming my grandpa’s name. Others cried after her, almost reaching her volume but not quite. I never knew what to do — crying is such a reserved act in the U.S. Overwhelmed, I constantly moved my head, looking around, to try to figure out my role in this. Was I supposed to be screaming too? My cousin, once, gently pushed the nape of my neck, indicating to keep my head bowed. It was like everyone had read some sort of funeral manual, and all I could do was grasp for my cousin’s hand and hope I wasn’t making a fool out of the family.

Afterwards, and every night, we held a vigil. During the first one, my dad told me, “They were alarming the village. Your aunties, they’re making sure everyone knows someone’s passed away. It’s a really old tradition, and not everyone agrees you should do it anymore. But your aunties thought it was a good idea to do it anyway.” Not my mom, though. Her tears were quiet ones.

At some point, my parents decided they wanted to diversify their vacations, so we stopped going back to China during the summers. In this last decade, I’ve only been back three times, the third time being for my grandfather’s funeral. When I was in my early teens, I thought nothing of it. But as I got older and older, I became more suspicious. My dad once remarked, “You know, when I first met your mom, she used to tell me that China had no culture. She would say, ‘Look at all these other countries. They all have their dancing and singing and look at us! We have nothing!’”

My parents grew up in poverty during some of China’s toughest times. They were born at the tail end of the Great Chinese Famine, and lived through Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution. My parents were only able to go to college as a result of a government sanctioned program that they had to go through rigorous testing and interviews to get into. My mom was the first woman in her small village to go to college; my dad was the first person to ever leave for Beijing, “the big city,” and eventually America. When you go back to their old high school, there are pictures of them on the school wall, proudly labeled as “notable alumni” — all because they escaped. It makes sense, then, that we stopped going back to China as I got older, when the familial obligation died down. They escaped, why would they want to go back?

“She doesn’t even belong here. She can’t speak Chinese. What a waste,” some man grumbled to the air in my grandma’s living room.

It takes a lot of audacity to claim that a granddaughter doesn’t belong at her grandfather’s funeral. I think he assumed I couldn’t understand Chinese.

When I told my sister what this man had said to me, indirectly or not, she was immediately furious. “How dare he say that when people are grieving?” she fumed. “Don’t pay any attention to him. You just remember that even at 17, you are more educated and more skilled than he will ever be.”

She didn’t mean it, she was just mad. I know because she later admitted how ashamed she was to lash out like that. “We can’t help that we were born from parents that have stable, well-paying jobs. We will always have more privileges than the majority of the people here, you remember that.”

What my sister felt that day is what writer Cathy Park Hong would call “political shame.” It’s a kind of shame that manifests from not knowing your place in a social hierarchy, being both the afflicter and afflicted of stifling social expectations. For my sister and me, it’s knowing that even though we will never measure up to our white colleagues, we will also never have to work nearly as hard as those in the Chinese countryside to earn a livable wage. For my parents, it’s knowing that they’ve turned their backs on their families and on their pasts in order to have a so-called “better life” and yet have to endure being called racist slurs at their workplace. The shame you feel when you trip and fall in front of people eventually dissipates. Political shame follows you everywhere.

On the last day of my grandpa’s funeral, we had to take his body to the crematorium and watch it be put into the oven. The people that worked there asked if we would like to keep the bones. There was a deeply uncomfortable silence for a few seconds before my grandma declined. His bones were put into the urn with the rest of him.

Once the process was done, we took the urn to an expansive field in the middle of nowhere. My uncle dug a hole into the grass before planting my grandfather down into the ground. “We would normally bury his body, but there are too many people to bury now, so the government says we have to use ashes to save space,” my cousin told my dad who told me.

My uncles heaped piles and piles of dirt on top of my grandfather’s ashes to form a small hill. They staked a modest gravestone into the side of the hill. Again, confused and uninformed as to what I was supposed to be doing, I followed my cousin to the ground where we kneeled and prayed three times over. Lastly, my aunts passed around fresh fruit and buns to throw on top of the grave, giving my grandfather sustenance on his journey towards the other realm.

The week following we revisited his grave to give him more food. Chinese folklore says it takes a year for the body to reach heaven, so the family has to visit every weekend for a year to make sure he has enough food. Once we were there, I was surprised that my aunts and uncles didn’t clear away any of the rotting food that had started to attract flies. It seemed disrespectful, but tradition is tradition.

Chinese funerals are better than American funerals in my opinion. American funerals only last a day and then you’re expected to move on with your life. At least with Chinese funerals, you are so overwhelmed by the grief and spectacle of it all that, by the end, you’re too tired to be sad. The biggest difference between the two, though, is how death is treated. White people are so scared of death, they want the corpse tucked away and gone as soon as possible. In a Chinese funeral, the corpse stays out in a refrigerated casket for a week.

Chinese funerals are about confronting abjection, or the discomfort one feels from being separate. After all, the corpse, as philosopher Julia Kristeva says in her essay Powers of Horror, is the “utmost abjection.” Kristeva argues that the best examples of abjection happen when you are confronted by things that represent a transitional state, a corpse representing the transitional state between life and death.

Abjection and shame go hand in hand. They are both unwanted feelings that stem from a state of middle-ness. They both deal in the transition that convinces you that you are both good and not good enough, ensnaring you in the worst case of learned helplessness. Abjection is the feeling of displacement in a country that doesn’t accept you but isn’t out to kill you; shame is the realization that you’ve resigned yourself to accept those bounds. And in the middle of all that is guilt. If abjection stems from expectation, as in the expectations that a culture or a country sets for a person, and shame stems from failure, as in a failure to break out of the restraints of expectation, then guilt rests in between.

Guilt is a strange emotion. It’s why my mom, despite wanting so badly for me to fit in with my white peers, still kept trying to instill aspects of Chinese culture into me. And why she felt so desperate to take care of my grandpa on her own during his last days. Guilt is perhaps the most burdensome of all emotions. The problem isn’t that it feels bad; it’s that you’ve done something to make you feel good, and the feeling good feels bad. My mom was comfortable with her life in America, and resentful of her harsh upbringing in China, so she was content with letting go. But Chinese culture holds onto things, every little thing. There was the expectation that she would raise Chinese children and uphold Chinese values, but she was okay when she didn’t do either. And when her father died, and she suddenly had to confront that she let go a little too much, she was overwhelmed with guilt.

Now, as I grow older, that guilt has transferred onto me. On my college admissions essays I boasted about being a unique candidate having grown up in an Asian American family, and being the unfamiliar face in a white community. And yet, in college, I try to set myself apart from the Asian international students in fear that I will be drowned out in the sea of faces that my TAs will inevitably confuse me with. Despite my family’s roots, I can’t guarantee that once my parents die I will want to visit China anymore. I can’t even communicate with my extended family, so what’s the point? The guilt lingers because I have paradoxically become accustomed to Chinese culture while separating myself from it. Have I turned away too much in my attempt to find success in this country? This is a uniquely first-generation American problem. No one else has to pick and choose the pieces of their culture that they want to keep or want to discard.

My sister once asked my parents if they would like a traditional Chinese funeral or an American funeral when they’ve passed. My mom frowned and scolded her to not speak of such things. I think she didn’t want to talk about it because she’d feel bad regardless of what answer she’d give. When my parents die, I think I will find some relief, perhaps in an unfounded hope that the guilt will die with them.

It’s not that I want to feel relief. I just don’t know how to find freedom otherwise.